Deceiving Grooves; Who Did it Better?

Earlier this summer a post titled “Adjustable Bounce; Who Did it Better” pitted Acushnet against Bridgestone in a death match concerning the best adjustable bounce wedge (perhaps slightly overly dramatic). Today we tackle a different issue, perhaps a sensitive issue for some (not me, of course), regarding men and their desire to have things appear larger than they actually are. Come on; I am talking about grooves and today the competitors are Cobra Golf and Karsten (aka PING).

So, back in November of 2012 I reported on a Cobra Golf patent application directed to a groove design that would provide golfers with the perception of larger grooves. Now golfers are a pretty gullible group of people, but would the perception of larger grooves, even though you know they aren’t any larger, actually make you play better? Would I run any faster if I used a stopwatch that ran at half speed so it seemed like I was running twice as fast, even though I knew the stopwatch simply ticking the seconds off twice as slow? I wouldn’t bet on it.

Well, even though I thought the idea was a bit loopy and something you couldn’t market without essentially calling a golfer stupid, not every one agrees. In fact, Karsten had a patent application publish this week as US Pub. No. BACKGROUND

[0003] In general, a golf club includes a club face with grooves in order to increase the frictional force at impact between the club face and the ball. The United States Golf Association (USGA) publishes and maintains the Rules of Golf, which govern professional golf in the United States. Appendix II to the USGA Rules provides several limitations on the grooves for golf clubs, including limitations on symmetry, width, depth, edge radius, and relative distance between grooves. The Royal and Ancient Golf Club of St. Andrews, which is the governing authority for the rules of professional golf outside the United States, provides similar limitations to golf club design.

[0004] Moreover, an accurate hitting stoke is accomplished through a variety of subjective, as well as objective, golf club features. For example, many people subjectively associate smaller grooves with decreased ball spin at impact and with shorter distances after impact.

.

.

.

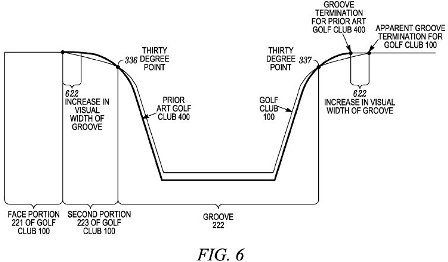

[0041] FIG. 6 illustrates an example of a cross-sectional view of the second part of club face 111 superimposed over a part of a prior art club face. As shown in FIG. 6, the use of second portion 223 in addition to groove 222 can create a visual impression to the user of golf club 100 that grooves 222 are larger than prior art grooves by amount 622 while golf club 100 and grooves 222 still comply with the USGA Rules of Golf. Accordingly, because many people associate larger or wider grooves with increased spin at ball impact and also with longer distances after impact, use of golf club 100 can provide an increased psychological benefit to its users and allow the user to hit a golf ball further and with improved accuracy.

.

.

.

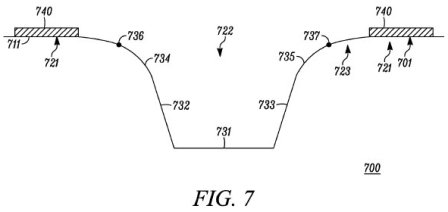

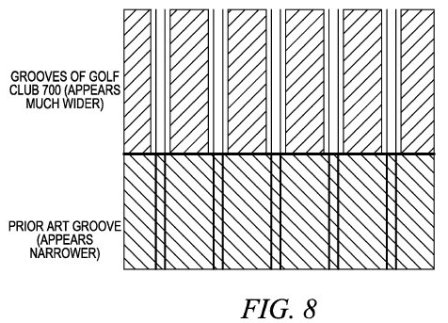

[0049] As shown in FIG. 7, golf club 700 is comprised of a contrasting finish, and a lead-in design for the grooves. The lead-in design, combined with the contrasting finish, creates an exaggerated “visual width” of the grooves, while the grooves remain entirely conforming to the USGA groove rules.

[0050] The contrasting finish is made up of a first finish (i.e., the lack of cover layer 740) and a “second finish” (i.e., cover layer 740) on club face 711. To manufacture golf club 700, the golf club head is forged or cast without the grooves in club face 711. After several smoothing steps, the golf club head possesses the natural finish of the metal, which is the first finish. Then a coating, or otherwise contrasting second finish, is placed on the golf club head. This contrasting second finish could be a plating, thin film coating, oxidation process, blasting process, or any other method that can, in some examples, create a resilient and thin coating. In many examples, the second finish is a contrasting finish when compared to the first finish that is created on the substrate club head material after the grooves have been machined or otherwise created. The contrasting second finish (i.e., cover layer 740) can be very thin to facilitate the milling of the lead-in design (in some examples, less than 0.001 in. (0.025 mm) thick). Some examples of contrasting finishes are: black-nickel chrome, dark-colored physical vapor deposition (PVD), QPQ (quench polish quench), oil can, satin nickel-chrome, steel shot bead blasting, or ceramic media blasting.

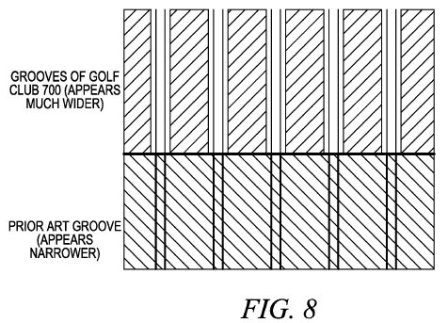

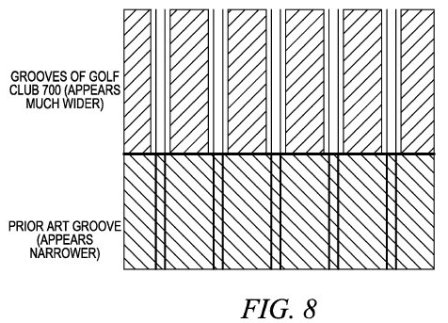

[0051] Referring to FIG. 8, a golf club with a first and second finish and the lead-in groove design is shown side-by-side with a standard finish and standard grooves. In this embodiment, the grooves of golf club 700 appear to be 20% wider than the grooves in the prior art golf club.

So, who did it better? I am not sure either did it better, so I give the win to Cobra Golf since they filed a patent application roughly a year before Karsten. Now I am off to purchase a muscle suit to wear during my round tomorrow because I am sure it will make me hit the ball further (and with improved accuracy)!