I’m Just Launching a Golf Knick-Knack Product; I Don’t Need to Worry About Patent Infringement

Yes, I have heard words to that effect many times. Well, perhaps this case will change your mind. How much money do you think could be at risk selling a novelty divot repair tool?

The case of Divix Golf Inc. v Jeffrey P. Mohr, et al. gives us a glimpse at why intellectual property is important no matter what type of products are being sold.

A recent III. DISCUSSION

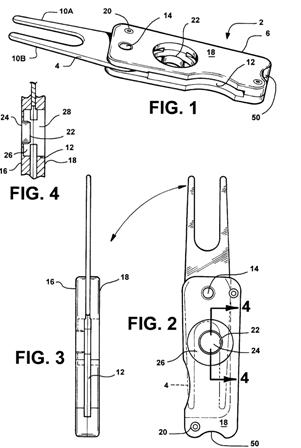

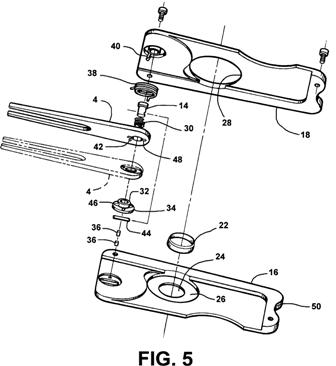

The device at issue in this litigation is a switchblade style ball mark repair tool’ sold under the name “divix.” The United States Patent and Trademark Office issued patent number 6,162,137 (` 137′) for this device on December 19, 2000. The ‘137 patent has 14 claims. Prior to trial, the parties stipulated on the record before Magistrate Judge Cathy Bencivengo that if this Court found the subject patent valid and enforceable, defendants infringed on Claims 1 and 8-14 of the patent. In that stipulation, the parties also acknowledged that ofthe fourteen claims in the patent, Claim 1 is the only independent claim. Thus, a finding that Claim 1 is valid and enforceable necessarily means all the dependent claims in the patent are also valid and enforceable. The Court will therefore address Claim 1 first.

.

.

.

The Court makes the following additional findings of fact with respect to the damages phase of this trial:

1. Defendants Jeffrey Mohr (“Mohr”), Remedy Golf, Inc. (“Remedy”) and Bandwagon, Inc. (Bandwagon) stipulated that they infringed Claims 1 and 8 through 14 of the ‘137 Patent if the Court found those claims valid and enforceable.

2. The “accused products” referred to in the infringement stipulation are Remedy’s switchblade divot repair tools which have the same detent mechanism as the patented Divix switchblade divot repair tools.

3. Mohr initially viewed the ‘137 Patent in late December 2000 or early 2001.

4. Mohr was interested in selling the divix as early as March 2001 and sent samples of the Divix to a manufacturer to obtain an estimate of production costs without authorization from or by Divix.

5. Mohr was President of Divix from January 2003 until his termination in June 2004.

6. As president of Divix, Mohr learned Divix’ manufacturing techniques, processes, and manufacturing know-how, had access to all of Divix’ books and records, and was privy to all of Divix’ contracts, agreements, customer lists and customer relationships. Additionally Divix’ sales representatives reported to Mohr.

7. While president of Divix, Mohr determined and controlled the pricing of Divix products and created Divix’ pricing structure.

8. During Mohr’s tenure at Divix, he became aware of competing switchblade divot repair tools in the marketplace and consulted Divix’ attorneys about whether those tools infringed the ‘137 Patent.

9. As a result of the conversations Mohr had with Divix’ attorneys about the potential infringement of the ‘137 patent, Mohr authorized cease and desist letters to other manufacturers of switchblade divot repair tools.

10. Turnamics, Inc., the manufacturer of the Zivot, a switchblade divot repair tool that competes with the divix, received a cease and desist letter from Mohr.

11. In response to Mohr’s cease and desist letter, Turnamics filed an action for declaratory judgment in a North Carolina federal district court to have the ‘137 Patent declared invalid.

12. As part of that litigation, Mohr reviewed affidavits from various Turnamics personnel who claimed that Harvey Speigel, the founder of Turnamics, created the Zivot in the early 90s.

13. Mohr subsequently spoke to Harvey Speigel about the circumstances surrounding his

invention of the Zivot.

14. Mohr claimed he believed the ‘137 Patent

was invalid based on his review of affidavits from Turnamics personnel and discussions with Harvey Speigel.

15. Thereafter, Mohr did not consult with an attorney regarding the possible invalidity of the ‘137 Patent.

16. Mohr sent a letter to Greg Bark, one of the Divix founders, in February 2004 which

states:

Given that, there is no long term future for the two of us to participate in Divix Golf, Inc. One of us has to go. If you go, Divix survives, GT Knives does not go Bankrupt and you and Todd don’t lose your collateralized property, at least not for awhile. If I go, Divix will collapse, and not just because my leadership is crucial at the moment but because I will actively make sure that it does. Let me remind you that I do not have a non-compete clause in my contract. Divix does not have an International Patent. Nor do you and Todd have the financial wherewithal or will to defend a challenge to your Domestic Patent by me, the employees and the Reps, in concert with new financial backers with a competitive, low cost, offshore product.

17. While President of Divix, Mohr ordered molds for Divix’ switchblade divot repair tool, known as the “divix” from Bandwagon in late February or early March 2004.

18. The target date for production of the switchblade divot repair tools based on these molds was August 2004.

19. After Mohr left Divix, a dispute arose between Mohr and Divix as to who owned the molds that Mohr ordered from Bandwagon.

20. Bandwagon sent Divix samples based on the molds ordered by Mohr but refused to send the actual molds.

21. Mohr formed Remedy in September 2004.

22. Remedy paid Bandwagon in the fall of 2004 to source its molds for switchblade divot repair tools in China.

23. Bandwagon was the middleman between Remedy and the Chinese manufacturers ofthe switchblade divot repair tools.

24. Remedy began receiving switchblade samples from Bandwagon in October 2004.

25. Bandwagon began sending Remedy switchblade type divot repair tools in late December of 2004.

26. The process for obtaining a final switchblade divot repair tool from Bandwagon is as follows: Once molds are requested from Bandwagon, it takes about ninety days to obtain a prototype, first-article sample. An initial sample is then sent to the purchaser who makes comments about the items that need to be corrected. The purchaser then sends the corrections back to Bandwagon who will then resend the corrected version to the purchaser. Once a sample receives final approval, it takes approximately eight weeks to get a production model that can be sold. The overall process takes about eight to nine months.

27. Remedy received tools based on the molds ordered from Bandwagon in November 2004

by January 2005, five to six months faster than usual production time.

28. Instead of using new molds, Bandwagon modified the molds it made for Divix’

switchblade divot repair tools to make Remedy’s switchblade divot repair tools.

29. The switchblade divot repair tools that Remedy received from Bandwagon were offered

for sale and sold in the United States.

30. The approximate number of Remedy switchblade divot repair tools with mechanisms

identical to the divix that were imported by Bandwagon is 60.000.

31. Approximately 10,000 more tools with mechanisms similar to the divix were imported

by Bandwagon for Remedy.

32. The mechanism in the switchblade divot repair tools that Remedy received prior to June 2005 differed from the mechanism in tools Remedy received after June 2005 only with respect to its size.

33. Todd Jones purchased a Remedy switchblade divot repair tool on June 3, 2005 that was

made from the Divix mold Bandwagon modified for Remedy.

34. Remedy received 500 switchblade-type divot repair tools from a company called

Advanced Plastics that were a knockoff of the divix.

35. Remedy distributed the switchblade divot repair tools from Advanced Plastics to its sales representatives to determine whether customers would be interested in a tool with a cigar-cutter.

36. Remedy received another shipment of switchblade divot repair tools in late 2006 or

early 2007 from the Chinese company Master Year.

37. Between January 2005 and July 2009, Remedy sold 108,984 infringing tools for a total

sale value of $609, 237.54.

38. The terms “Switchblade” and “Folding Divot” in the “Memo” category on Remedy’s Sales Summaries Charts used by plaintiff’s expert Randall Smith and those items designated as SB under the “Inventory” column indicate accused products.

39. Sales of the divix account for 96% of plaintiff’s overall sales.

40. Plaintiffs gross profit between January 1, 2005 and August 2007 is 70%.

41. Plaintiff’s total income on all items sold between January 1, 2005 and August 2007 is $126,893.

42. Plaintiff’s profit margin on all goods sold is 4.1%.

43. The prices charged by Remedy to former Divix customers were between 25% and 50% below prices charged by Divix.

44. Remedy’s average selling price was approximately 40% below Divix’s average selling price between January 1, 2005 and May 31, 2006.

45. Forty-Six percent of Remedy sales during the period between January 1, 2005 and May 31, 2006 were to Divix’ former customers. Twenty-Eight percent of Remedy revenues during the period January 1, 2005 through May 31, 2006 were from plaintiff’s former sales representatives.

46. Many Div ix sales representatives are independent contractors who are allowed to work with the company of their choice.

47. The ultimate purchasers of the switchblade divot repair tools have relationships with individual sales representatives rather than specific companies; however, the purchaser contracts with the company rather than the representative.

48. Plaintiffs expert testified that a typical manufacturing company has between forty and fifty percent gross profit and that percentage would merit a royalty rate between six and ten percent.

49. Plaintiff’s expert testified that gross profit is more important than actual profit in determining a royalty rate.

50. Plaintiff filed the instant lawsuit against defendants on July 26, 2005.

51. The Court issued the Markman Order construing the claims in the ‘137 Patent on February 13, 2007.

52. The Court issued its order finding the ‘137 Patent not invalid based on inequitable conduct on January 6, 2010 and its oral ruling finding the ‘137 Patent valid and enforceable on July 28, 2010.

53. As of September 1, 2010, Mr. Mohr and Remedy had not informed any resale purchasers that the accused products infringed on the ‘137 patent.

54. The accused products were still listed on Remedy’s website as of September 1, 2010.

55. There were at least two other switchblade divot repair tools on the market besides those manufactured by Divix and Remedy during the period of defendants’ infringement.

56. A unit royalty of $1 would bring the cost of the switchblade divot repair tool manufactured by Remedy to the approximate manufacturing cost of the Divix switchblade divot repair tool.

57. The sales figures for Divix’ switchblade tool listed in Divix’s sales summaries, $2,529,560, are lower than the sales figures on Divix’ profit and loss statement, $2,823,452.22.

58. The sales figures listed on Divix’ profit and loss statement are the most accurate.

59. The gross profit listed on Divix’ profit and loss statement is for all Divix items sold, rather than just Divix’ switchblade divot repair tool.

60. Plaintiffs expert did not verify the profit and loss statements provided by Divix.

61. Plaintiffs expert used factors other than those identified in the AICPA to determine the appropriate royalty rate.

62. Mohr and Remedy willfully infringed the ‘137 Patent.

63. The conduct of Mohr and Remedy with respect to the infringement of the ‘137 Patent

is exceptional.

.

.

.

Based on the foregoing, the Court finds that Claim 1 of the ‘137 patent is valid and enforceable. As Claim 1 is the only independent claim in the ‘137 patent, the Court further finds that the remaining dependent claims of the ‘137 patent, Claims 2-14, are valid and enforceable. Due to the pre-trial stipulation filed by defendants Mohr, Remedy and Bandwagon, the Court finds those defendants have infringed Claims 1, and 8-14 of the ‘137 patent. The Court enters a damage award of $121,847.50 against defendants Mohr, Remedy and Bandwagon.’ Further, an enhanced damage award equal to two times the amount assessed shall be entered against defendants Mohr and Remedy for a total of $243,695.02. Plaintiff shall submit briefing with respect to its attorney’s fees no later than thirty days from the date of this order. Finally, defendants are permanently enjoined from advertising, manufacturing or selling any products that infringe the ‘137 Patent.

I think there may be a lesson or two to learn from this golf patent litigation story!

Dave Dawsey – The IP Golf Guy